Antibiotic-resistant superbugs are under increasing threat from a new copper surface which kills bacteria 100 times faster than the standard copper.

The collaboration between RMIT University and Australia’s national scientific agency, CSIRO, resulted in the new copper product. These findings were published.

Copper has been used for many years to combat different strains, including golden staph. The ions that are released from copper’s surface are toxic to bacteria cells.

This process is slow if standard copper is used. Professor Ma Qian, RMIT University, explained that this is why significant research is underway to speed up the process.

Qian stated that a standard copper surface would kill 97% of golden staphy within four hours.

“Incredibly, when we placed golden staph bacteria on our specially-designed copper surface, it destroyed more than 99.99% of the cells in just two minutes.”

“So not only is it more effective, it’s 120 times faster.”

These results were important, Qian said, without any drug.

He said, “Our copper structure has shown itself to be remarkably potent for such a common material.”

Once further developed, the team thinks there will be many applications for this new material, including antimicrobial door handles and other touch surfaces in homes, schools, hospitals and public transport as well as filters in antimicrobial respiratory systems or air ventilation systems and face masks.

The team now plans to examine the effectiveness of the enhanced copper against SARS-COV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19), and also assess 3D-printed samples.

Another study suggests that copper is highly effective against the virus. The US Environmental Protection Agency approved copper surfaces earlier in the year.

A unique structure that uses more copper in the fight

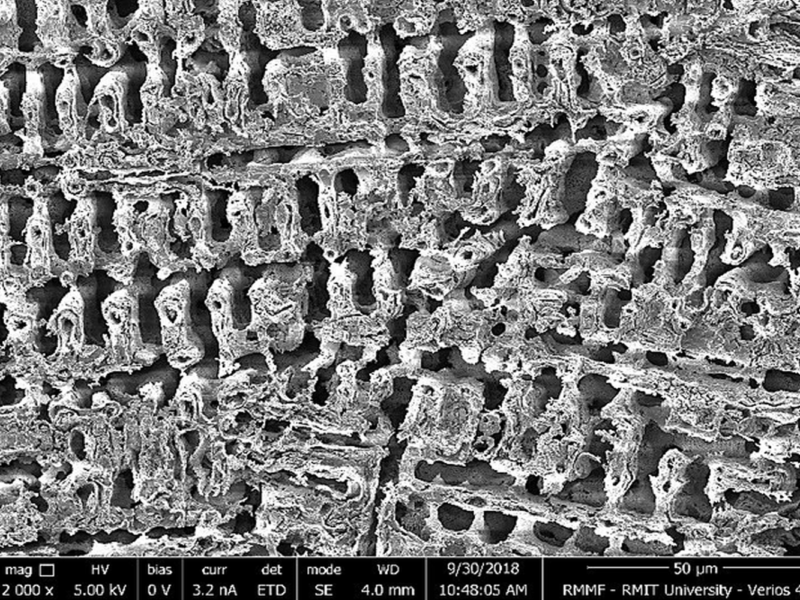

Jackson Leigh Smith, the study’s lead author, stated that copper’s unique porous structure is key to its effectiveness in killing bacteria quickly.

The alloy was made using a special copper mold casting process, which arranges copper and manganese molecules into specific formations.

The manganese atoms were then extracted from the alloy by a simple and cost-effective chemical process called “dealloying”. This left pure copper with tiny microscale and macroscale cavities on its surface.

Smith stated that copper is made up of microscale cavities that look like combs and inside each tooth there are smaller nanoscale cavities. It has a large active surface area.

“The pattern also makes it super hydrophilic or water-loving. Water lies on it as a flat movie, not as droplets.”

“The hydrophilic effect means bacterial cells struggle to hold their form as they are stretched by the surface nanostructure, while the porous pattern allows copper ions to release faster.”

Smith stated that “these combined effects not only cause structural decay of bacterial cell, making them more susceptible to poisonous copperions, but also facilitates uptake copper ions into the bacteria cells.”

“It’s that combination of effects that results in greatly accelerated elimination of bacteria.”

Dr Daniel Liang, CSIRO, said that researchers around the globe were searching for new medical materials and devices to reduce the spread of superbugs resistant to antibiotics.

Liang stated that drug-resistant infections are increasing and that there is limited availability of new antibiotics. Therefore, Liang believes that the development of bacteria-resistant materials will be a key component in addressing the problem.

“This new copper product offers a promising and affordable option to fighting superbugs, and is just one example of CSIRO’s work in helping to address the growing risk of antibiotic resistance.”

This research was started by an RMIT-CSIRO PhD Program and was then co-funded, in part, by the CASS Foundation Melbourne. Patents are pending in Australia, China, and the USA for this innovative process.