More living organisms on our bodies and in our homes could help in combating diseases — if we let them live

Do the same laws of biodiversity which apply in nature also apply to our own bodies and homes? If so, current hygiene measures to combat aggressive germs could be, to some extent, counterproductive. So writes an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution. They propose that examination of the role diversity of microorganisms plays in the ecosystems of our bodies and homes should be intensified. The findings could challenge existing strategies for fighting infectious diseases and resistant germs.

Ecosystems like high-biodiversity grasslands and forests are more resistant to disturbances, such as invasive species, climate fluctuations and pathogens, than lower-diversity ecosystems. If this diversity is reduced, basic ecosystem functions are lost. This so-called stability hypothesis has been proven in hundreds of biological studies. This research mainly deals with the world of animals and plants, but when looking at our own body or home through a microscope, an equally diverse community of microorganisms is revealed. Potentially, similar laws could apply to these communities as to the ‘big’ ecosystems, and this could have far-reaching consequences for our health care.

Researchers at the iDiv research centre propose, in an article published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, that the theories of ecosystem research should also be tested on our immediate environment and its microorganisms.

“We influence this micro-biodiversity on a daily basis, especially by combating it with, for example disinfectants and antibiotics – actually with the aim of promoting good health,” says ecologist Robert Dunn, professor at North Carolina State University and the University of Copenhagen. Dunn wrote the article during a one-year sabbatical stay at iDiv – in collaboration with iDiv scientist Nico Eisenhauer, professor at Leipzig University. “This interference in microbial species compositions could impede the natural containment of pathogens,” says Eisenhauer.

According to the ecological niche theory, plants and animals apportion the available resources in their habitat among themselves, whereby species with similar needs compete with each other. Newly arriving species find it hard to gain a foothold, at least in a stable ecosystem. However, in species-poor ecosystems or those disturbed by humans, non-native species can invade much more easily.

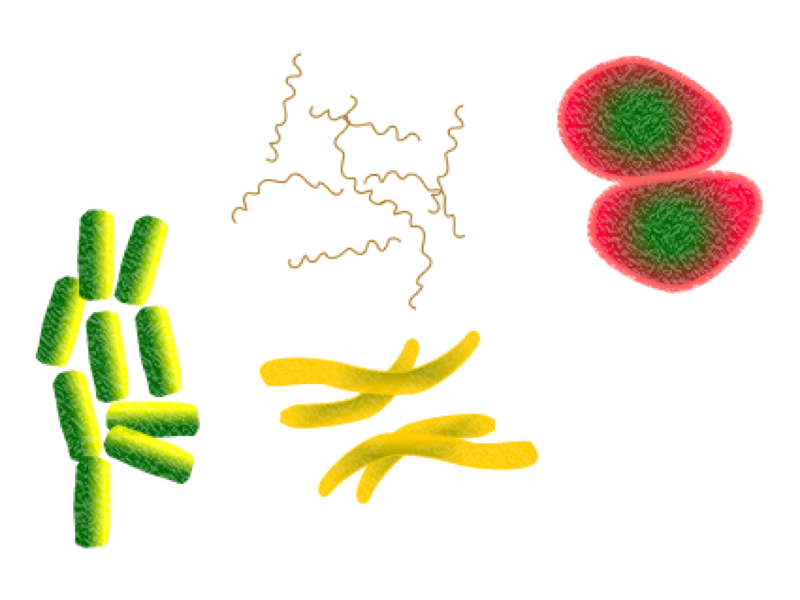

Microorganisms also form their own ecosystems. So far, more than two hundred thousand species are known to live in human dwellings as well as on and in human bodies. Bacteria in human dwellings account for half of these, and thousands of bacteria live on our bodies. In addition, there are around forty thousand species of fungi in our homes, although these are less likely to be found on human bodies.

“Pathogens in our environment are comparable to invasive species in nature,” says ecologist Nico Eisenhauer. “If you transfer the findings from large habitats to the world of microbes, you have to expect that our habitual use of disinfectants and antibiotics actually increases the dispersal of dangerous germs because it interferes with the natural species composition.” As an example, this has been documented for rod bacteria of the species Clostridium difficile, which causes intestinal inflammation with diarrhoea. The use of antibiotics enabled these to spread faster. So-called non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTMs), which form a biofilm primarily on shower heads and can cause diseases, are predominant in chlorinated water. They are largely free to proliferate on metal shower hoses, while plastic shower hoses, which encourage a rich community of microorganisms, have lower levels of NTMs.

Bacteria communities which prevent disease can also be actively created. For example, in the 1960s, researchers discovered that babies whose noses and navels were inoculated with harmless strains of the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus were rarely colonised by S. aureus 80/81. This bacterium can cause diseases ranging from skin infections to life-threatening blood poisoning and pneumonia. Another example is faecal bacteriotherapy; by transferring a healthy community of microorganisms from person to person, it is possible to treat intestinal infections.

So, is our fear of ‘Bacteria & Co.’ unfounded and our knee-jerk reaction to fight them actually dangerous? “We are not physician,” says Eisenhauer. “I would certainly not recommend a surgeon to work non-sterile on the open body. Having said that, as far as surfaces are concerned, targeted inoculations with a selected microbial community could possibly prevent the spread and establishment of dangerous pathogens.”

In any case, only a relatively small proportion of the microorganisms in our environment actually causes disease. This also applies to insects and other arthropods, usually regarded as pests in flats and houses – especially spiders. As hunters, they provide important ecosystem services by exterminating mosquitoes, bedbugs, cockroaches and house flies, which can actually transmit diseases. “We just have to let them be,” says Robert Dunn.

How the theories of biodiversity and ecosystem research apply to the health sector should, according to the three authors, be systematically investigated. Eisenhauer suggests, firstly, to test in which microbial communities common pathogens can spread better or worse on surfaces.

Source: German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv) Halle-Jena-Leipzig

Journal: Nature Ecology & Evolution

Funder: German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research Halle-Jena-Leipzig, German Research Foundation, European Research Council