In a new study, researchers at the Biodesign Institute explore a safe and simple treatment for one of the most devastating and perplexing afflictions: Alzheimer’s disease (AD).

Lead authors Ramon Velazquez and Salvatore Oddo, along with their colleagues in the ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research Center (NDRC), investigate the effects of choline, an important nutrient that may hold promise in the war against the memory-stealing disorder.

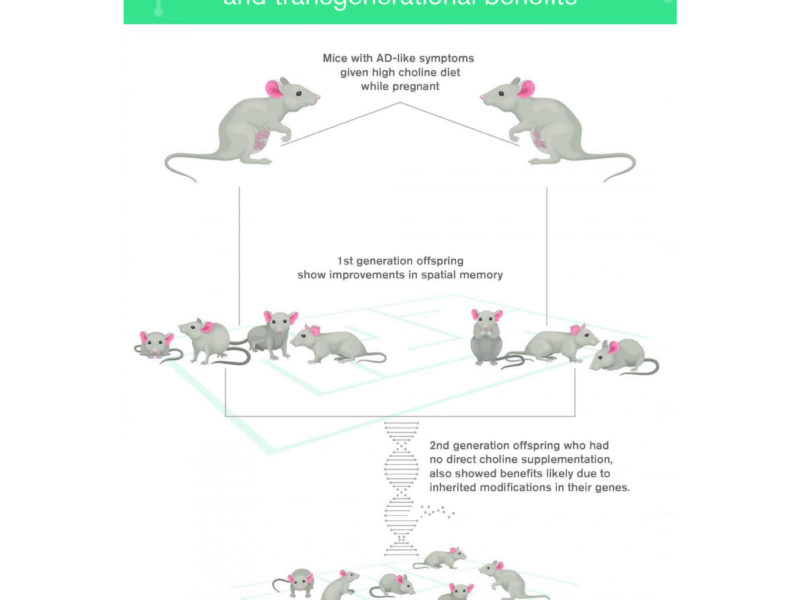

The study focuses on mice bred to display AD-like symptoms. Results showed that when these mice are given high choline in their diet, their offspring show improvements in spatial memory, compared with those receiving a normal choline regimen in the womb.

Remarkably, the beneficial effects of choline supplementation appear to be transgenerational, not only protecting mice receiving choline supplementation during gestation and lactation, but also the subsequent offspring of these mice.

While this second generation received no direct choline supplementation, they nevertheless reaped the benefits of treatment, likely due to inherited modifications in their genes.

The exploration of such epigenetic alterations may further exciting new avenues of research and suggest ways of treating a broad range of transgenerational afflictions, including fetal alcohol syndrome and obesity.

Supplementing the brain

Choline acts to protect the brain from Alzheimer’s disease in at least two ways, both of which are explored in the new study. First, choline reduces levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that can act as a potent neurotoxin, contributing to the hallmarks of AD: neurodegeneration and the formation of amyloid plaques.

Homocysteine is known to double the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease and is found in elevated levels in patients with AD. Choline performs a chemical transformation, converting the harmful homocysteine into the helpful chemical methionine.

Secondly, choline supplementation reduces the activation of microglia–cells responsible for clearing away debris in the brain. While their housekeeping functions are essential to brain health, activated microglia can get out of control, as they typically do during AD. Over-activation of microglia causes brain inflammation and can eventually lead to neuronal death. Choline supplementation reduces the activation of microglia, offering further protection from the ravages of AD.

The findings appear in the current issue of the Nature journal Molecular Psychiatry. The NDRC researchers were joined by co-authors from the Translational Genomics Research Institute in Phoenix. (Oddo is also a researcher with ASU’s School of Life Sciences.)

Unremitting devastation

Alzheimer’s disease is now believed to begin its path of destruction in the brain decades before the onset of clinical symptoms. Once diagnosed, the disease is invariably fatal, shutting down one vital system after another. Mental decline is relentless, with patients experiencing a range of symptoms that may include confusion, disorientation, delusions, forgetfulness, aggression, agitation, and progressive loss of motor control.

The disease is poised to afflict 13.5 million people in the U.S. alone by mid-century if nothing is done to address the disease. The staggering costs of Alzheimer’s are projected to exceed $20 trillion in the next 40 years. Developing effective treatments rooted in a more thorough understanding of this complex disease is one of the most daunting challenges facing modern medicine and the global healthcare infrastructure.

Altered states

Research into the origins of Alzheimer’s disease strongly suggests that a great variety of factors are at play. While advancing age remains the greatest risk factor, other hazards that have been implicated in the disease include genetic predisposition and lifestyle.

To this end, studies suggest that diet can have a significant effect in increasing or lowering the risk of cognitive decline, and the risks may be transmitted across generations. A classic case is known as the Dutch Hunger Winter–a severe famine in 1944-45 that affected pregnant women and their offspring.

When a recent study examined the adult health records of those born in the Netherlands during this period, results suggested that the severe dietary deprivation endured by the mothers of these children heightened the occurrence of obesity, above-average LDL cholesterol and, intriguingly, schizophrenia in their offspring. Mortality after 68 years of age increased by 10 percent in this population. It is believed that these adverse health effects occur as a result of the silencing of genes in unborn children. These health-related genes remain silenced throughout life, leading to poor health outcomes.

On a more hopeful note, a healthy diet has been shown to offer protection from diseases, including cancer and Alzheimer’s disease. Patients following a Mediterranean diet for 4.5 years lowered their risk of AD by 54 percent. Another study pointed to the effects of a Mediterranean diet rich in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, legumes and nuts, as well as fish and poultry in reducing the accumulation of Aβ-amyloid, the protein responsible for plaque formation.

Effects of choline

Choline is a vitamin-like essential nutrient that is naturally present in some foods and also available as a dietary supplement. It is a source of methyl groups needed for many steps in metabolism. All plant and animal cells require choline to maintain their structural integrity.

Choline is used by the body to produce acetylcholine, an important neurotransmitter essential for brain and nervous system functions including memory, muscle control and mood. Choline also plays a vital role in regulating gene expression.

It has long been recognized that choline is particularly important in early brain development. Pregnant women are advised to maintain choline levels of 550 mg per day for the health of their developing fetus. “There’s a twofold problem with this,” lead author Velazquez says. “Studies have shown that about 90 percent of women don’t even meet that requirement. Choline deficits are associated with failure in developing fetuses to fully meet expected milestones like walking and babbling. But we show that even if you have the recommended amount, supplementing with more in a mouse model gives even greater benefit.”

Indeed, when the AD study mice received supplemental choline in their diet, their offspring showed significant improvements in spatial memory, which was tested in a water maze. Subsequent examination of mouse tissue extracted from the hippocampus, a brain region known to play a central role in memory formation, confirmed the epigenetic alterations induced by choline supplementation. Modified genes associated with microglial activation and brain inflammation, and reduced levels of homocysteine resulted in the observed performance improvements in spatial memory tasks.

Due to the epigenetic modifications induced by choline, the improvements carried over to the offspring of mice receiving supplemental choline in the womb. “We found that early choline supplementation decreased homocysteine while increasing methionine, suggesting that high choline levels convert homocysteine to methionine,” Velazquez said. “This conversion happens thanks to an enzyme known as betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (BMHT). We found that choline supplementation increased the production of BMHT in 2 generations of mice”

The study’s significance is two-fold, establishing beneficial effects from nutrient supplementation in successive generations and proposing epigenetic mechanisms to account for the reduction of AD memory deficit in mice. “No one has ever shown transgenerational benefits of choline supplementation,” Velazquez said. “That’s what is novelabout our work.”

Choline is an attractive candidate for treatment of AD as it is considered a very safe alternative, compared with many pharmaceuticals. The authors note that it takes about 9 times the recommended daily dose of choline to produce harmful side effects.

Future work will explore the effects on AD of choline administered in adult rather than fetal mice. The authors stress however that while results in mice are promising, a controlled clinical trial in humans will ultimately determine the effectiveness of choline as a new weapon in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease.

Source: Arizona State University

Journal: Molecular Psychiatry

Related Journal Article: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-018-0322-z