Feeling stressed or anxious makes people more able to process and internalise bad news, finds a new UCL-led study.

The Wellcome-funded research, published in The Journal of Neuroscience, reveals that a known tendency of people to take more notice of good news than bad news – the optimism bias – disappears when people feel threatened.

“Generally, people are quite optimistic – we ignore the bad and embrace the good. And this is indeed what happened when our study participants were feeling calm; but when they were under stress, a different pattern emerged. Under these conditions, they became vigilant to bad news we gave them, even when this news had nothing to do with the source of their anxiety,” said co-lead author Dr Tali Sharot (UCL Experimental Psychology).

Previous studies have shown that people are more likely to incorporate information into their existing beliefs if the information is positive. Such optimism can be good for well-being and keep people motivated, but can be unhelpful when people underestimate serious risks, so the researchers were seeking to understand if the general human tendency to prioritise good news might vary depending on other conditions.

The study was conducted in two parts: one in a UCL lab, and one with firefighters in Colorado.

In the lab, half of the 35 participants were told at the start that they would need to deliver a speech on a surprise topic in front of a panel of judges after completing a task – thus elevating their stress levels – while the other half were told they would complete an easy writing assignment at the end of the study. The heightened stress among those anticipating public speaking was confirmed by measures of physiological arousal (by testing their skin conductance and cortisol levels) and self-reported anxiety.

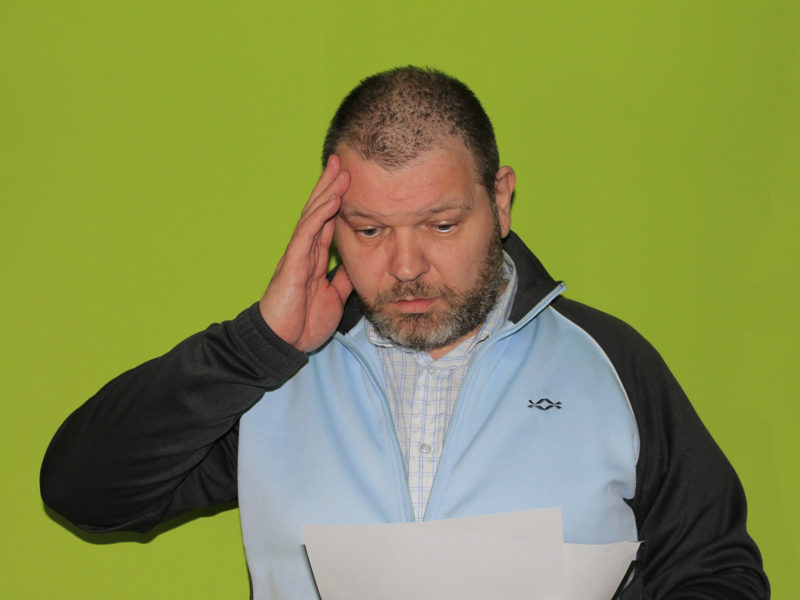

For the task, the participants were asked to estimate the risk level of various threatening life events, such as being a victim of domestic burglary or credit card fraud. They were then told the real risk – either good news or bad news depending on how it compared to their estimate. Later on they were asked to provide new estimates of what they thought the risks would be for themselves.

As expected, the participants who were not stressed (more relaxed) internalised the good news better than the bad news. Researchers found these participants continued to underestimate some risks even when being told the threatening event was more likely than they thought.

People who were stressed or anxious were better than the more relaxed participants at incorporating the bad news into their existing beliefs, while still responding normally to good news.

The study was replicated with similar findings in a real-world setting with firefighters, who did the task online while they were on shift between calls at the station. Their anxiety was measured by self-report, and varied naturally due to their volatile work environment.

The researchers say their findings help explain how people benefit from a generally optimistic way of processing information, while still taking heed of warning signs when under threat.

“A switch that automatically increases or decreases your ability to process warnings in response to changes in your environment might be useful. Under threat, a stress reaction is triggered and it increases the ability to learn about hazards – which could be desirable. In contrast, in a safe environment it would be wasteful to be on high alert constantly. A certain amount of ignorance can help to keep your mind at ease,” said co-lead author Dr Neil Garrett, who conducted the study at UCL before moving to Princeton University.

Source: University College London

Journal: Journal of Neuroscience

Funder: Wellcome

Related Journal Article: http://www.jneurosci.org/content/early/2018/08/06/JNEUROSCI.0716-18.2018